Mizoguchi: Secrets of the exquisite image

Saturday | May 10, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

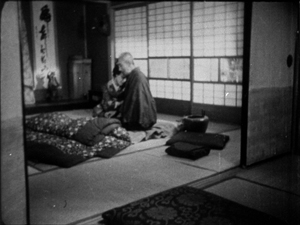

Sansho the Bailiff (1954).

DB here:

First things first: Happy birthday, Mizo-san! (He was born on 16 May 1898.)

Secondary things second: This entry is based on a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, as part of its comprehensive Mizoguchi retrospective. I want to thank my friends David Schwartz and Aliza Ma for inviting me to MoMI.

A fragile and fragmentary legacy

Mizoguchi, age twenty-eight, and Sakai Yoneko at Nikkatsu studio, 1926.

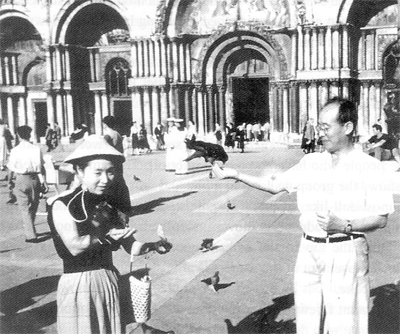

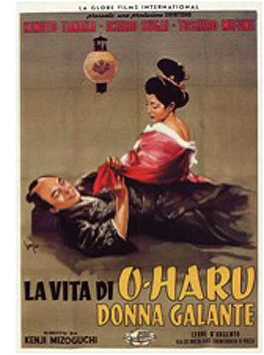

Mizoguchi Kenji’s renown in the West has flowered and faded. Like other Japanese directors, he was unknown in Europe and America before 1950. When Rashomon won the Golden Lion at Venice that year, Japanese cinema sprang onto the world’s radar. Just two years later, Mizoguchi began winning top Venice prizes with Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), and Sansho the Bailiff (1954). His old associate Nagata Masaichi saw export opportunities in Japanese costume pictures, especially after Gate of Hell (1953) won the Academy Award, and so Mizoguchi turned out several historical films with high-tone production values. He died in 1956, after Street of Shame (1956), a return to contemporary social commentary.

In just five years, this flare of attention and the praise of the Cahiers du cinéma critics made him second only to Kurosawa in Western recognition. During the 1960s, while Japanese critics were writing him off as outdated, international critics canonized him. Here’s Andrew Sarris in 1970.

I recently saw an obscure Mizoguchi film at New York’s Museum of Modern Art without any English subtitles, which left me up the Sea of Japan without a paddle. The program notes alerted me to the plot outline, but I was generally puzzled by the personal relationships, and the picture dragged along. . . . And then at the end the beleaguered heroine walks to a restaurant on a hillside overlooking the sea, and she orders something from a waiter in white, and the camera is high overhead, and the morning mists are bubbling all around, and the camera follows the waiter as he walks across the terrace to the restaurant and then follows him back to the heroine’s table now magically, mystically empty. It is as if death had intervened in the interval of two camera movements, to and fro, and the bubbling mists and the puzzled waiter provide the Orphic overtones of the most magical mise-en-scène since the last deathly images of F. W. Murnau’s Tabu.

Mizoguchi’s reputation was based almost completely upon his 1950s work. But as ever, film distribution shaped film tastes. Soon after the 1972 success of Tokyo Story in New York, Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films began circulating many major Japanese titles. Most electrifying for my generation was an abundant set of Ozu films, the arrival of which coincided with Donald Richie’s Ozu (1974). Twenty years after Mizoguchi’s emergence, Ozu began his ascent to the top of the pantheon.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

A broader recognition of 1930s-1940s Japanese film was crystallized in the 1978 publication of Noël Burch’s book To the Distant Oberver: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film. Burch urged the case that Ozu, Mizoguchi, and other “mature” directors had done their most ambitious work well before the Western festivals and critics had caught up with them–that in fact the venerated postwar films were mannered and unadventurous compared to the artistically radical prewar work.

Since then, as Ozu (and Naruse, and many more) have risen to the pantheon, Mizoguchi has become quite obscure. Critics haven’t really boosted him much; his most famous film, Ugetsu, ranked 50th in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll. Nor is the range of his work easy to sample on video. In 1976, Kristin and I were obliged to go to London to see the early Ozus not in US distribution; now, everything is on DVD. But many years later I went to Brussels for a complete Mizo retrospective, and the rare titles I saw there remain nearly unknown. His festival classics and the “Talbot canon” circulate on good-quality prints and DVDs, thanks to Criterion and Janus. But other films must be hunted down in obscure foreign DVD.

Worst of all, the survival rate of Mizoguchi’s films is appalling (although not exceptional for Japan). He made 43 films between 1923 and 1929; of these, only one survives complete. For the rest of his career he made or contributed to 42 features, of which we have 30. We lack over half his output. The physical quality of what we have varies a great deal, from gorgeous (Genroku Chushingura) to appalling (The Straits of Love and Hate, 1937, blown up from a scratched and contrasty 16mm copy). In fact, copies seem to have deteriorated. Prints I saw in the 1970s of Oyuki the Virgin (1935) were in decent shape, but many copies circulating now seem to be bad dupes of those prints, now much battered. There seems to be no systematic effort to restore what we have.

Tears are easy; tragedy is hard

I can’t deny that Mizoguchi’s fluctuating reputation is due to more than availability. He is easier to admire, even to worship, than to love. His films, though visually sumptuous, can be somber and bleak. Often unremitting tales of suffering, they lack humor (though not irony). Ozu’s mix of poignancy and comedy is much easier to enjoy than Mizoguchi’s forbidding, near-tragic despair. Ozu is also a more rigorous stylist; his signature is in every frame. While Mizoguchi was no less distinctive, he was more pluralistic in his technique.

Another obstacle: despite working with melodramatic material, Mizoguchi cools it down, sometimes to the point of remoteness. For many of his films, the prototype was Japan’s shinpa drama, an early twentieth-century theatrical tradition that blended kabuki themes and situations (e.g., the conflict of love and duty) with Western-style dramaturgy. Shinpa plays tended to concentrate on the sufferings of women in a male-dominated society. Shinpa women are victimized, exploited, and condemned; when they sacrifice themselves for men, too often the men attack them, betray them, or dump them. Mizoguchi worked many variations on these plot elements. When the American Occupation demanded more liberal films from the industry, he simply let the oppressed woman win some victory in the end.

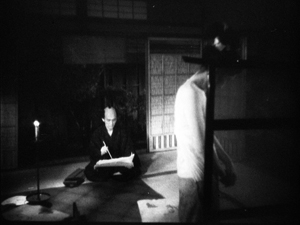

Whether the woman wins or loses, Mizoguchi refuses to beg for tears. Some directors, notably Sirk, amp up melodrama; others, like Preminger, bank the fires. Mizoguchi seems to try to extract the situation’s emotional essence, a purified anguish, that goes beyond sympathy and pity for the characters. In The Poppy (1935), here’s how he renders the moment at which a father and daughter learn that the daughter’s suitor has abandoned her. The core dramatic action is the daughter moving from the foreground to console her father, at which point they embrace.

Some climax! No close-ups, no fast cutting, no camera movement; people withdraw from us and leave us on the outside. All of which suggests that one dimension of Mizoguchi’s artistry consists of exploring how human emotions, notably the unhappier ones, can be expressed in vivid, sometimes surprisingly “cold” pictures.

Pictures tell the story

Everybody grants that Mizoguchi makes magnificent images. He has gone down in history as a pictorialist. But his pictorialism is of a peculiar kind. We tend to think of pictorialist filmmakers as, for instance, masters of landscape, like Ford in My Darling Clementine; or exponents of abstract patterning, like von Sternberg in Shanghai Express; or buccaneers of aggressive depth, like Welles in Citizen Kane.

On each of these possibilities Mizoguchi can match the masters. Here’s a landscape from Portrait of Madame Yuki (1950; this is the scene that made Sarris swoon), a geometrical shot from Hometown (1930), and a bold depth composition from Naniwa Elegy four years before Kane.

It’s not surprising that Mizoguchi relies on the image; in his youth he studied painting (interestingly, Western-style painting at that). But he is, I think, a more fervent pictorialist than his peers.

Most movie scenes consist of a story situation mapped onto the space; the style follows, emphasizes, or shapes the story’s presentation. Suppose, Mizoguchi seems to ask, that we start with an image and ask it to become a drama. That’s in a sense what seems to happen with the Poppy example above: a striking picture develops into a story through a suite of compositional changes. Or consider this, from Sansho the Bailiff. A scene starts with a bundle of brush in a village street. Gradually it becomes the site of action: two children peep out, one by one.

Our view isn’t impeded only by the brush. A man bursts eagerly into the frame, blocking the boy and girl, followed by another man. The camera tracks a bit around the foreground post. As the scene goes on passersby will intrude into the frame.

You can’t, I think, imagine many more ways to suppress our views of the kids. We strain to see past all these obstructions, and when the view finally clears and the children are visible and come forward briefly, they turn from us…and more people pass in the foreground.

This is actually an important moment in Sansho the Bailiff: The children, kidnapped from their mother, are about to become slaves. It could be rendered with all the stops out, as a scene of brutality or high tension, but instead Mizoguchi let the dialogue (after some delay) explain what’s happening. At first you might think that Zushio and Anju have escaped from their captors and are in hiding; the unfolding image initially permits that possibility. Eventually, though, the shot, expressing the children’s fear and shame as they shrink from not only the men but the camera, holds us in its own right.

Instead of an image that is a vehicle for the story, the story is gradually born out of the changing image. To some degree, this happens in many films, but not with the persistence and rigor we find in Mizogcuhi. He talked of wanting to hypnotize the viewer, and this is done, I think, as much by the minute changes in the pictures as by the dynamics of the drama.

This version of pictorialism employs several strategies. I’ll mention just three.

Now you see it, sort of

Kiyonaga Toru, Interior of a Bathhouse (1780s).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Traditional Japanese cinema is itself heavily pictorial, from the zigzag excitement of the 1920s swordplay films to the dynamic modernity of the city dramas and the monumental gravity of historical dramas. Directors, I’ve argued in various places, cultivated a “decorative” approach to technique. Composition, camerawork, cutting, and other tactics often created flashier compositions than we find in other national traditions. As early as 1922, Ikeda Yoshinobu was creating arabesques with a bedstead, framing the faces of grieving family members (Cuckoo).

The gridded zones of the Japanese house seems to have invited filmmakers to explore a sort of Advent-calendar style, with bodies framed in different apertures (The Abe Clan, 1938). The same idea could be applied to a bar’s Art Deco wall divider (First Steps Ashore, 1932).

I’ve also argued that this love of pocketed compositions may be an effort to echo similar impulses in Japanese graphic art. The Kinoyaga woodblock print above, with its partial views of women bathing and the little windows through which we see the male attendant watching, is a beautiful example. Perhaps filmmakers adapted this eye-beguiling tactic as a way of giving cinema some cultural credentials (if not a national identity).

Most directors don’t sustain such flashy compositions. The shots function mostly as long-shots or establishing shots, or as in the Cuckoo example, as a series of brief extracts from the larger scene. Mizoguchi drew upon this decorative tradition but let it be sustained through figures moving into and out of the apertures within the frame. He creates a game of vision, a sort of fluctuating pictorial vividness that conceals or reveals or teases us with information.

One of the most vivid examples comes in this famous scene from Sansho the Bailiff. Tamaki’s leg tendons are cut, and the other enslaved women are forced to witness it. As the struggling Tamaki is peeled away from the wall and the slavemaster walks to her offscreen, the other women become visible and an older master comes slightly forward in the central square Tamaki had occupied.

As she screams, the grid isolates each woman’s fearful turning away. As with the earlier Sansho scene, dialogue comes to “button up” the unfolding of the image: The old man tells the cringing women that all runaways will punished this way.

The impact of the act is amplified not by, say, cutting to different women’s reactions, but by letting us see them all, simultaneously, in a choreography of terror.

Mizoguchi finds an abundant variety of ways to play his game of vision. Not only are figures and faces secreted in various pigeonholes of the frame, but he can tease us with some that are merely shadows or partial figures (The Poppy; Tokyo March, 1929). Sometimes the key element, such as a character’s reaction, is obscured by a semi-transparent surface, as when the embarrassed model is caught in a corner of a screen in Utamaro and His Five Women (1946).

What other directors treated as piquant flourishes, imaginative ways to arouse our visual interest before moving in to closer views, Mizoguchi saw as a way to activate any cranny of the image and invest it with expression. But for that process to unfold, he needed time.

Intensify and prolong

From the brief surviving fragment of Tojin Okichi (1930).

During the course of filming a scene, if an increased psychological sympathy begins to develop, I cannot cut into this without regret. I try rather to intensify and prolong the scene as long as possible.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Mizoguchi is famous as an exponent of long-take shooting. His earliest surviving film, Song of Home (1925) displays the Hollywood-style editing that most Japanese filmmakers mastered at the period. At some point–he says it was while shooting Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner)–he began using a method he called “one scene, one cut.” (Here “cut” apparently refers not to a shot change but to a single take, like a “cut” of meat. Hollywood filmmakers talked the same way sometimes.) That would suggest that he took every scene in a single shot, but actually he didn’t. Most of his scenes are built out of several shots, and throughout his career he would have recourse to standard analytical and shot/reverse-shot cutting for many sequences. He wasn’t as strict about the plan-sequence as, say, the Miklós Jancsó of the 1960s and 1970s was.

Still, he definitely used longer takes than most filmmakers of his day. The shots in most of his post-1935 films average between twenty-five and forty seconds in length, which means that some shots run minutes. Many of his long takes are made from static camera positions, as in the above examples. But he didn’t shrink from camera movements, either tracking shots or crane shots. Kristin and I discuss an example from Sisters of Gion in Film Art, and in his later films he enjoyed establishing a setting with a high-angle crane shot before moving in to details. He also enjoyed riding the crane and directed from it even if the shot was static.

Fixed frame or moving shot, Mizoguchi’s long takes can extract an arc of pictorial-dramatic intensity. That arc can have a clear-cut ABA pattern. In My Love Has Been Burning, the liberal feminist Eiko finds her weak lover Hayase drunk and despondent. He’s no longer the idealist she thought he was, but he defends himself as changing with the times.

Hayase says he’s got some money now and they can marry. When she doesn’t warm to the idea, he attacks her, and suddenly her face gets enlarged, upside down, when he slams her to the floor. This is the first high point of the scene.

They struggle out of frame, but Mizoguchi doesn’t follow them.

Immediately there’s a second assault on our vision: a screen abruptly crashes into the foreground.

After it settles into place, Eiko flees back into the frame, pausing by the doorway. She leaves, and Hayase totters to the same spot looking after her.

The shot has built up to one spike, the image of Eiko on her back, her face close to us, and then to a second, with the collapsing screen. At the end, the site of action returns to the beginning: a figure near the doorway, something else (Hayase, the screen) in the foreground. But in the course of this ABA pattern, the game of vision has concealed as much as it has revealed.

Throughout his career Mizoguchi experimented with the patterning of his long takes, often building them around advances to and away from the foreground, as in these examples. This tactic can be seen in a pure state in the most intense scene of the Occupation feminist film Victory of Women (1946). Here the characters rush the camera and shrink from it as the emotional pitch rises.

Tomo’s husband has just died, and she has already told her friend the lawyer Hiroko that she has no more milk for her baby. Tomo calls on Hiroko, who invites her to come in. The camera obediently tracks back as she enters and sits.

Hiroko, at first oblivious to the distraught Tomo, begins to question her. At first Tomo says that nothing has happened to her baby, and she slides away from Hiroko. She tells her that her husband died the day that they had met in the street. She edges closer to the camera.

Sobbing, she tells Hiroko that the baby is dead; he died sucking her breast. She falls out of the frame and as the camera pulls back Hiroko bends to comfort her. But she also asks Tomo to tell her exactly what happened.

Tomo confesses that staring at her crying baby, she hugged it so close that she may have killed it. As she rises, she cries, “My baby!” And she turns and staggers, like Ayako in Naniwa Elegy, to the most distant point of the set–as if hoping to escape both Hiroko and the camera.

Track in as Hiroko goes back to her, at the spot at which the shot’s action started. Once more the two women advance to the camera, with Hiroko nearly dragging Tomo back to the center. But when Hiroko suggests she go to the police, Tomo slides quickly away from her, back to us, and the camera abruptly pulls back to accommodate her. As when the paper wall crashes into the frame in My Love Has Been Burning, a spike in the drama is accompanied by a second burst into the foreground.

Hiroko rushes to embrace Tomo, assuring her that “You must not run from life, but face it!” Mizoguchi’s staging favors the doubt and fear on the face of Tomo, not the somewhat complacent Hiroko.

As Hiroko hurries off to dress for going out, Mizoguchi’s camera lingers on Tomo, not only pitiable but justifiably worried that she is condemned. As she bends and glances to and fro, Mizoguchi ends the seven-minute scene on an image of a woman with nowhere to turn. This is a terrifying final image: Is this what Hiroko meant by “facing life”?

Some of Mizoguchi’s earlier works go further still. Instead of a coming-and-going pattern, in which the characters confront the camera and then retreat, we get a going-and-going one. The most famous, about which I’ve written probably more than I should, comes in Naniwa Elegy, when Ayako, telling her boyfriend of her sexual infidelity, retreats from him, and from us.

A Western director–Wyler, say, as in The Little Foxes, or Huston–would have put the camera at exactly the opposite point, in the corner of the wall, so that Ayako would advance toward us and Nishimura’s reaction would be constantly visible in the background. It’s as if Mizoguchi anticipated such full-disclosure framing (before these men had even made their films!) and dismissed it as too easy. By suppressing characters’ expressions, he throws our attention onto Ayako’s voice and her posture, while also sustaining some suspense about how Nishimura will respond to her revelations.

Mizoguchi finds a huge variety of ways of turning images into drama, and he has left us a rich repertory of staging strategies–if we only look. Young filmmakers, are you looking?

Filigree

Tanaka Kinuyo and Mizoguchi Kenji in Venice, early 1950s.

[The long take] allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Once Mizoguchi enhances the decorative frame with surfaces and holes bristling with possibilities, and once he sustains it in time through the long take, he can build his scenes out of slight changes in the image–changes that add nuance and expressive depth to the drama. We’ve seen this already in several passages, but I want now to stress how this sharpens our attention and engagement. The restraint of Mizoguchi’s handling (restraint within sumptuousness, I should say) trains us to watch for the tiniest shift in pictorial emphasis. This is the third strategy I want to mention.

In Lady of Musashino (1951), minor changes around the deathbed drive our eye to the profile of the dying Michiko.

Likewise, when Oishi in Genroku Chushingura reads the master’s poem, sent to his vassals after his suicide, he lowers the paper just a little at the climax, and the gesture is echoed in the men’s slumping forward even more. (This is a movie largely made of just-noticeable differences.)

The just-noticeable differences can be triggered by tiny changes in the avenues of our vision. In Street of Shame, the brothel owner, turned from us in the middle ground, first reveals Mickey and the delivery boy down the left corridor. When he shifts his head, Mizoguchi closes off that view and allows faces and bodies of the prostitutes to fill up the corridor on the right.

Bolder movements can yield even briefer glimpses. When Oharu reads the message from her dead lover, Mizoguchi gives us a “decoy” shot: Her mother stands guard on the left and in the distance we see the door through which the father is expected to come. But the scene’s real action is taking place behind the hanging kimono, where Oharu reacts painfully to the letter. Since we can’t see her, only her wavering voice and the trembling of the kimono convey her emotion. Suddenly she starts to thrash around, her mother leaps toward her, and a tussle ensues. The kimono is pulled down in a heap.

What’s all the fuss? What is Oharu doing? The answer is given to us in an almost subliminal detail, the knife that flashes through the lower right corner of the shot in only two frames on the 35mm print. Oharu races out of the shot, bent on suicide.

So the nuances that spring up may be protracted or simply glimpsed, but either way they become the product of the image giving birth, through its transformations, to the drama. The strategy is just as applicable to closer views as to long shots. In one scene of Woman of Rumor (1954), the keeper of an elegant brothel notices a young man getting cozy with her daughter. The tension is exacerbated by the fact that she hopes to nab Dr. Hatoba herself. As the two talk, Mizoguchi buries Hatsuko in the rear of the scene, her presence signaled by a shadow and her kimono sleeve poking out from a screen.

Mizoguchi cuts directly in and provides a medium-shot of Hatsuko peeking. This might seem safe and conventional, especially in the light of daring choices like those made in Naniwa Elegy. But Mizoguchi now wants to trigger the game of vision around the woman’s face and the edge of the screen. As she listens, he teases us with a little suite of changing expressions and minute gradations of partial blockage–a sort of pictorial vibrato.

As Hatsuko edges out to approach the couple, Mizoguchi switches our attention to small, nervous hand gestures.

Once installed behind the couple, Hatsuko starts the whole process again, from eye-catching sleeves to peekaboo eavesdropping.

Mizoguchi was a fairly pluralistic filmmaker, so the strategies I’ve itemized don’t exhaust everything we encounter in his movies. Sometimes he builds scenes in a fairly orthodox way, with traditional framing and cutting. But taken as a whole, his films offer a magnificent repertory of ways in which the image can, under pressure, deepen and enrich a dramatic situation. Unlike most of today’s filmmakers, he cares about rigor, nuance, and austerity–while at the same time working with scenes of intense emotion. Admire him, worship him, love him, or just respect him: film culture can’t live fully without him.

Thanks, over forty years of viewing, to the Japan Society of New York, the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute (formerly the Japan Film Library Council), Dan Talbot and José Lopez of New Yorker Films, and the Brussels Cinematek, especially Gabrielle Claes.

The MoMI series runs until 8 June. It begins on 16 May at the Harvard Film Archive and on 19 June at Pacific Film Archive. For Fandor’s Keyframe daily, David Hudson has a varied roundup of response to MoMI’s series.

Both Criterion and Masters of Cinema offer many Mizoguchi films on DVD, some on Blu-ray. See also Criterion’s Hulu Plus offerings. Digital Meme sells DVDs of some early Mizoguchis, with benshi accompaniment; the exasperatingly brief fragment of Tojin Okichi is on volume 2..

My quotation from Andrew Sarris comes from “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1970,” in The Primal Screen (1973), 60-61.

Good clichés will never die as long as journalists need to crank out copy. The MoMI retrospective has revived the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi tug-of-war, this time among New York critics (here and here). Such sideswipe critiques and hosannas can’t really be backed up within the space limits of popular publishing. Moreover, I think that such quick assertions of taste block close consideration of the work. Once you’ve dismissed a filmmaker, you’re unlikely to probe further, and your readers will probably be even less curious. I defected years ago from the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi skirmishes.

The fact that every decade or so Mizoguchi is “rediscovered” through a retrospective indicates his elusive reputation. Among English-language scholars, the 1980s was the big period. Dudley Andrew wrote a still indispensable reference book on Mizoguchi in 1981, and Keiko McDonald offered a penetrating critical survey in 1984. Both volumes, now rare and costly, deserve to be made available in digital editions. Robert Cohen’s two-volume dissertation “Textual Poetics in the Films of Kenji Mizoguchi” (UCLA, 1983) was also significant. Since then, incredibly, we have had only one more overview in English, Mark Le Fanu’s Mizoguchi and Japan, along with an in-depth analysis of some 1930s films, Don Kirihara’s award-winning Patterns of Time. Sato Tadao’s monograph was published in Japanese in 1982, but it’s only recently been available in (a somewhat problematic) English translation (as Kenji Mizoguchi and the Art of Japanese Cinema). Two of my stills are drawn from this book. The French have been more consistently productive, with several studies over the years. A thorough account in Spanish is by the prolific Antonio Santos.

For some background on Western rankings of Mizoguchi, Kurosawa, and Ozu, see this interview with the late Hiroko Govaers. Hiroko was instrumental in bringing many classic Japanese films to Europe and the U.S.

Some of the material in today’s entry comes from Chapter 3, “Mizoguchi, or Modulation,” of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. That offers a much fuller account of what I think Mizoguchi is up to, although today’s blog offers some points and examples not in the chapter. Offshoots of the book’s argument can be found in this online update, and in this blog entry, which compares Mizoguchi with his sort-of-rival Wyler. My oldest piece on the director, “Mizoguchi and the Evolution of Film Language,” in Stephen Heath and Patricia Mellencamp, eds., Cinema and Language (1983), 107–117, contrasts his work with Western practitioners of deep-space staging. Background on the “decorative” impulses in traditional Japanese cinema can be found in Essays 12 and 13 in my Poetics of Cinema, and in early portions of Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema.

P. S. 29 June: Thanks to Jeff Fort for correction of a title in the original blog post!

Sansho the Bailiff.